The train doors slid open, and I moved through them with everyone else towards the elevators up to the surface streets. We strangers waited in silence for the elevator to arrive. When it got there, those with bicycles entered first and the rest of us filled in around them, although there was still ample space. Someone leaned heavily against me despite the empty part of the elevator. I fidgeted to clarify with motion that I was not an elevator rail. The leaner’s back remained pressed into me.

“Excuse me? Hi, yes, I am a person, not a wall.”

The leaner looked around at me, then shuffled off a few feet away into the big open space in the middle of the elevator. My eyes met those of another person standing on the other side of the bicycles. This was a person who looked like a woman in this culture just like I did, with eyes which held empathy for me. Silently, we admonished the patriarchy in that moment, both of us acknowledging and lamenting that this was the latest one in a series of events just like it.

That is what it is like to be treated the way USA culture treats a woman. To be unseen by men to the point of being treated like furniture in a very literal sense, and to have a sense of community with women which is quite unlike any other community that has welcomed me. American women’s culture has a lot more shared context than American culture in general, and that affects communication. A silent moment of eye contact and a pair of nodding heads with a particular facial expression was all it took for us to both know we were thinking about sexism, the atrocities of how women are treated, the obliviousness of men, and the fact that talking about it out loud in a closed space with this person still there was too dangerous to risk even with the other strangers present. After all, sometimes the people who do these things are also rapists and murderers. We’ve all heard the stories. The shared fear is part of the shared context.

Some years later, after I began my testosterone treatments but long before my facial hair grew in, I injured my foot. I was in a lot of pain, but I had an errand that could not wait. I dragged myself to the bus. As I entered, I saw someone rise from the handicap section and turn to talk to someone. I slid around behind the riser to take the only empty seat on the full bus, relieved by the instant reduction in foot pain.

“Hey! I was going to sit there!” said someone who looked like a woman. The person who had stood looked like a man, and had risen to give my admonisher the seat I occupied. Normally, I would have stood at that point.

“I have a foot injury,” I said. “I need to sit.”

“Yeah well I have had brain surgery!” the admonisher responded emphatically.

“Maybe if you ask someone else to stand up for you, they will,” I said.

The admonisher gasped and hemmed and hawed and made comments about how rude I was being, but did not ask anyone else to give up a seat. I looked down, unsure how to respond. After all, I had already mentioned my foot injury.

The admonisher fell silent and avoided looking at me until two stops later.

“Have a good day, Sir,” the admonisher said cheerily and exited. I was surprised by the complete 180 in how this person was treating me.

“I’m not a Sir!” I called out but it was too late; the person was gone.

It was not until that final exchange that I understood the conversation we had been having, because up until that point, I had thought that I was being perceived to be a woman. Women are so accustomed to being taken advantage of by men behaving in excruciatingly selfish ways that my admonisher probably did not believe that my foot was injured instead of taking my words at face value the way people had before I started testosterone. My lowered gaze was probably seen as an averted gaze, and that combined with my silence was probably interpreted as being yet again ignored by a man when trying to speak up about something important, rather than as the pensive confusion it was. If I had been seen as a woman, the other person might have recognized the confusion and checked in with me about a possible misunderstanding instead of continuing down a defensive path. The sudden cheery departure was probably a response to the common fear of being followed by a mean man from a bus.

I spent the rest of the bus ride disturbed by what had happened, and wondering how I was supposed to know how to interact with people if I can’t tell what gender they think I am. Even now after years of additional testosterone treatments, I still get both “Ma’am” and “Sir” every time I go to the grocery store.

The experience of being treated like a woman involves being ignored by more people than just men. Before I transitioned, I could say the same thing five times, in five different ways, trying desperately to get someone to listen to me, only to be either dismissed or totally ignored. I regularly spoke directly to groups or individuals of various genders and got silence in return, complete with a total lack of body language acknowledgement. I made regular asides to myself under my breath thinking no one could hear them.

Then I began my testosterone treatments. People started answering my muttered comments. I was astonished – and quite a bit embarrassed. Now, if I begin to speak, people of various genders will stop what they are doing to listen to me, even if I am not speaking to them directly. It’s as if I have stepped into a spotlight that follows me wherever I go. I intentionally relearned how and when to speak in order to handle that kind of power responsibly.

I do not believe that white cisgender men, having never experienced that contrast, understand the disproportionate power of their voices. And I don’t think most people recognize that they contribute to that power difference by listening to men and ignoring everyone else. Yes, non-men and feminists of all genders and political leanings do this too. After all, it is difficult to overcome cultural indoctrination. I am working to overcome this in myself by questioning whether I am truly listening with respect in my heart every time a woman speaks.

I refer to white cisgender men in particular above because cisgender men of other races are systematically silenced in a variety of contexts in ways that are often similar to what white women experience here in the USA. I recommend reading about that sometime.

My understanding of men’s culture is still in its infancy. The few all-men spaces I have been asked to join are uncomfortable for me. The values are so different from the values of women’s culture that I have trouble navigating these spaces due to the unfamiliarity. The things men do that I consider rude and hostile happen with far greater frequency in these spaces, and I wonder whether they see these things as rude and hostile. With the isolation caused by this pandemic, I have been unable to continue exploring these spaces. This is unfortunate, because that perspective would help round out this article.

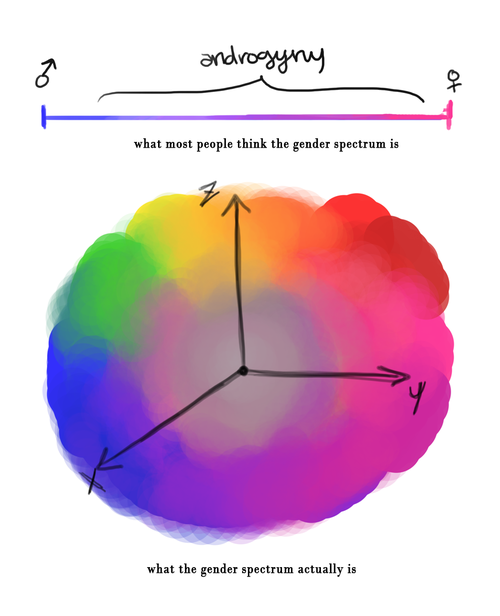

Men, women, and nonbinary people each have a very different set of shared experiential context to the degree that it has created separate co-cultures. This affects how people speak to each other within these groups and also between them. Men and women who can also be either cisgender or transgender, which creates an additional overlay of shared experiences, and this also impacts communication. Thus I have found that while I prefer to just let people make assumptions and not bother with filling them in about my gender, this creates communication issues because it means that strangers and I are not on the same page about which communication culture I am coming from. This, to me, has highlighted the very different co-cultures associated with genders here in the USA in a way that contradicts everything I was taught in school about how wonderful it is that we have gender equality here.

This topic was selected by the author’s Patreon patrons.